Concord

It is referring to the use of fonts from only one family. The example below uses variations of Helvetica to emphasize the differences between the heading and body texts. There is less fun in creating such designs but is also the safest approach to maintain an elegant and consistent look.

You may also want to take a look at the following related posts:

- How To Mastering Font Combinations

- Superfamily Typeface Font : 50 Serif and Sans Font Pairings

- 30 Fonts Everlasting A Life Time

- Top Typeface and Font Combinations Resources

- 100 Beautiful Typefaces For Professional Design

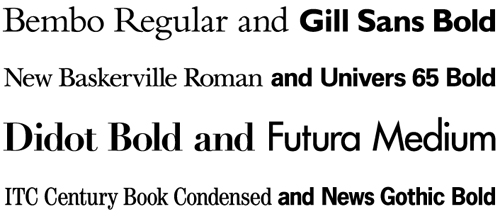

Contrast

It is about selecting fonts from different families, such as using a Sans Serif along with a Serif font or Oldstyle with Modern font. This is an interesting job where you can mix and match the various selections to form what you think is good and pleasing to the eyes. Below is an example of mix between Helvetica and Garamond.

Conflict

This is opposite of Contrast where the selection of fonts come from two similar families. The fonts have too many similarities that combining them will look more like an error, especially when placed in a single line. The example below shows the combination of Times New Roman and Garamond.

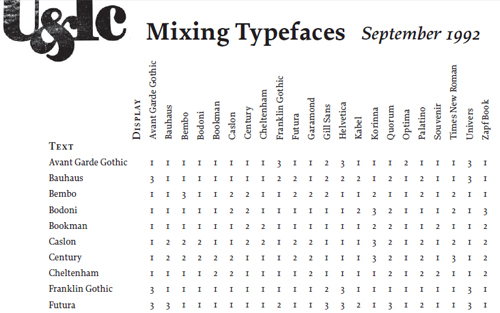

There are a lot more type families for us to play around with our combinations of course. Douglas Bonneville has suggested 19 best combinations made with the most popular fonts below.

Source: 19 Top Fonts in 19 Top Combinations

So what makes a good font combination? As mentioned right at the beginning of the article, there are no specific rules on matching the fonts. If a typography work has the ability to lead a reader’s eye with use of contrast and controlling the order on how the information is to be read, that is a fantastic mixture.